Overview

Chapter 4 details the fundamentals of commercial leases, and how they influence the value of a property. Both economic and non-economic lease terms are important. It is essential to understand different aspects of leases, the reasoning behind them, and the negotiating leverage of each party, all of which ultimately play into the contracted lease terms. To illustrate a commercial lease, this chapter walks the reader through the main terms addressed in a shopping mall lease.

Summary

Listen to this narration if you prefer

Rents negotiated between a tenant and a landlord determine the scheduled future cash flow of a property. Rents consist of 3 components: base rent, base rent escalations, and percentage rent. Percentage rent, also known as overage, is unique to retail rents and specifies the percentage of the tenant’s gross revenue that a landlord receives in addition to the base rent and escalations.

Operating expenses are comprised of two components: common area maintenance (CAM) and specific tenant expenses, as well as property taxes, insurance, and utilities. A lease will specify the cost allocation of these items between the landlord and the tenant. Generally, CAM expenses are divided between all tenants of a property, based on their respective pro-rata share of leased space, while each tenant pays directly for the costs incurred within their leased space. A retail lease will often specify requirements and cost allocations of other items such as marketing, HVAC, security, and property maintenance. These lease items will detail the level of service the landlord is obligated to maintain and who will pay for these services.

Tenant improvements (TIs) and free rent are concessions landlords make to attract and retain tenants. TIs are changes made to the leased space to satisfy the tenant’s fit-out preferences. These can include changes to the layout of the space or the addition of fixtures or infrastructure.

Net rent is the rent received net of all operating costs. Some leases are negotiated as “triple net” — meaning that all costs (including insurance, utilities, and property taxes) are passed through to the tenant. Net effective rent is a somewhat ambiguous term, but in this chapter, it refers to the rent net of unrecovered maintenance and operating costs, the amortized value of free rent, the amortized value of leasing commissions, and the amortized value of TIs. Figure 4.1 summarizes an example of how to calculate net effective rent.

It is important to note that non-economic terms are just as important as economic items when contracting tenants for a property, particularly in the retail sector. The second part of this chapter reviews, in detail, some important items that need to be correctly contracted into leasing agreements with retail tenants to ensure the success of the entire property. A landlord needs to negotiate clauses such as restrictions on signage, going-dark provisions, and defining hours and days of operation. Tenants may want to negotiate expansion rights and limit usage restrictions by the landlord. It is important to remember that most items negotiated in a contract are non-monetary, yet affect the underlying value of a property.

Questions

These are the types of questions you’ll be able to answer after studying the full chapter.

1. What are the three basic components of rent in a retail leasing agreement?

2. What incentive does a retail tenant have in paying percentage rent?

3. What is an anchor tenant?

4. What are TIs?

5. What is “triple net rent”?

6. What is a “radius restriction”?

Audio Interviews

Use of the leased space (4:36)

BRUCE KIRSCH: The other thing that you comment upon, relative to leases, other than rent– everyone always thinks rent and term are the most important elements of a lease. You suggest that the use of the space, as defined in the lease or not defined in the lease, can be the second most critical element in a lease. And–

PETER LINNEMAN: Oh, I’d even say in a retail lease it’s the most important element. And in a commercial lease, it’s probably the third most important after rent and term. Use of space is important. Think about it. This is my asset. And I’m not going to find– the first question is, what are you going to do with it?

BRUCE KIRSCH: Right.

PETER LINNEMAN: I mean, and you can– even in an office building, what, you’re going to grow mushrooms in it and use– bring in truckloads of manure in my office building every day and grow mushrooms in it? That’s going to have odors and so forth on other users. And it’s going to make my building a lot less attractive.

That’s my asset. And yes, you’re paying me, but you’re paying me a flow. I own the whole asset. The issue becomes even, you can imagine, in warehouses, if I have a nonsprinklered building, you can’t store flammables or fireworks or ammunition. Because I can’t have that.

Or you can have restrictions that you– I won’t take radioactive stuff and store it in my office buildings. I don’t want somebody doing radioactive research. And I mean, I don’t mean radioactive in the sense of formulas, I mean real research, splitting atoms. That’s my space.

Now, yes, these are extreme. But that’s why you take care of the extreme. Use is critical. You couldn’t pay me enough for some of the noxious uses. What, I’m going to let to Ku Klux Klan and the Nazis, and they’re going to be able to put their signs all over the place on my high-quality office building? Of course not. I mean, it will drive my business– it’s fine.

So I get an extra $3 a foot from the Ku Klux Klan and the Nazi to be in my prime building. And I have guys with white hoods and swastikas walking in all day– they’ll kill my building. I won’t be able to lease it. That’s my asset.

And then in retail, it’s just totally transparent that it all depends on synergies– great retail, at least, all depends on creating synergies– the shoe stores and the clothing stores and the sporting goods stores and the general good stores and the food and so forth and so on. And the example I always use is signage and the usage of my space becomes critical. Because you might do something that attracts a lot of people.

Let’s say, we put a firing range in the middle of the best shopping mall. You know, you rent 2,000 feet. You put a target range inside your 2,000 feet in my center. And then you put a big sign of naked people out in front of it.

You’ll destroy all of my normal retail business in a million square foot mall, because people are going to be offended by the pictures of naked people, though you might draw a bunch of 18 and 20-year-old guys with tattoos who want to shoot pistols. And so fine, they pay me $2 a foot extra on 2,000 feet, and 990,000 feet are being destroyed in the process.

It’s my space. What you do in my space, I got to make sure doesn’t destroy value. Now, as long as it doesn’t destroy value, then that’s less important. And that’s why in retail it’s more important because you don’t just– in office and warehouse, it’s noxious, it’s dangerous type of stuff I prohibit.

In retail, I got to make sure you don’t tell me that you’re opening up a food store, and then open up a shoe store instead. Because I’m trying to balance the number of shoe stores I have and the number of food stores I have. And that’s my job, and I need to control that.

Percentage rent (3:27)

BRUCE KIRSCH: It’s impossible to talk about the physical manifestations of properties without talking about leases. And so one of the things that we learn in the text is this notion of overage or percentage rent with respect to retail plazas. Can you just give a basic description of, why does it make sense for a landlord to essentially be able to take a tax on sales in a plaza?

PETER LINNEMAN: Well, it’s not a– it’s interesting. It’s more from the retailers point of view, namely, again, when I’m a retailer, and I’m renting from you– especially complex retail, highly interactive, highly spontaneous consumption retail– what I’m paying you for as a retailer is creating an environment that attracts customers. In other words, my Orange Julius stand or my little pizza stand is probably not going to attract a lot of people. Therefore, I need an environment that is quite rich.

And of course, every landlord is going to tell you, my retail environment attracts all these people, and everybody’s going to shop at your place. So you say, OK, fine, put your money where your mouth is. If you believe that people are going to come, then make some of the rent dependent on them coming, that is to say, on sales, because I believe I’ll get my sales if you can get people there. So to create a retail environment, to create those synergies, those positive spillovers between retailers, you make that rent.

Well, since– and if you think about, why aren’t there percentage rents in office? Well, everything’s internal. It’s not about, you created an environment where my business can occur. My business is occurring as Microsoft out there in the market somewhere, or if I’m an accounting firm, out there in the market. It’s not occurring because of your office space, whereas with retail, it is occurring because of the retail environment you create.

Similarly, my boxes are not being stored because you created a place where boxes can be stored. I got to store my boxes somewhere. So that’s why you’ll see percentage rents with the retailer basically telling the landlord, prove it to me. And that’s why the more complex the retailing is, the more I depend on a retail environment, the greater that there’s a reliance on percentage rents.

BRUCE KIRSCH: And so under that logic, in practice, do we see percentage rents ever in leases for the anchors, or is it just limited to the in-line tenants?

PETER LINNEMAN: It’s generally limited to the in-line tenants, because if I’m the anchor, I’m telling you, hey, I’m making the place. I’m the one bringing the customers with my sale advertisements, in particular. The anchor, yes, brings them, partly because I’m Macy’s or I’m a name that people recognize, but also partly because I’m the one who puts ads in the newspapers and on television and in stuffers saying, come shop, and our location is. I’m the one bringing them. So you don’t charge me percentage rents. You subsidize my rent, in fact.

Devil is in the lease details (5:30)

BRUCE KIRSCH: The devil’s in the details in all business. And the same goes for in leases and signing a contract for space. And one of the things that I would ask my students is, just for a show of hands, how many of you have ever truly read your apartment lease word for word, from start to finish? And you’ll get maybe 10% of the people.

And you know, it’s a boring, dry document. And so why would you read it? Well, you would read it because you’re promising to carry certain things out. And you don’t realize the seriousness of that until you get burned, like–

PETER LINNEMAN: Yeah, your percentage is higher than my percentage in my classes. Usually it’s maybe one person, sort of sheepishly. And then you find out they were a law student, and they were forced to do it for their class or something.

But it is. It’s a serious document. It’s a very serious document. You’re agreeing to some very serious things, and then you always get– even with the lease, you always get the people who said, oh, I didn’t know that I couldn’t leave early, or gee, I didn’t know I’m responsible for the damage if it’s greater than my deposit. I thought my deposit was all I was liable for. Or, you know, there’s a whole laundry list.

And not reading your lease is not a smart thing. It’s like not reading your loan document or your credit card. If you’re going to sign a credit card agreement with a credit card company, read it. And yes, most of it’s boilerplate. Fine. Know what it says your obligations are as a good idea in life.

And then on commercial leases, every once in a while you’ll run into somebody who hasn’t read their commercial lease. And either they’re buying a building and they haven’t read it, or they’re developing a building and they didn’t read it, and there are horror stories out there. And like most horror stories, they don’t happen very often, because most people have somebody who is knowledgeable really reading the lease, not just a lawyer, even, in some cases, an outside lawyer, but somebody in the firm who knows the normal way they conduct business.

And the horror stories are always things like, gee, I buy a building, I didn’t really read the leases carefully, nobody really went through them carefully, and I find out that one of the tenants has the right to leave with no penalty if their sales drop below a certain number, or a tenant– even in an office building, right, if their sales– or by the way, I find out that I just assumed it was Coca-Cola on the lease because Coca-Cola is renting, but it turns out it’s not Coca-Cola. It’s a special purpose entity company created by Coca-Cola for the sole purpose of leasing this space for Coca-Cola. And then you find out, gee, they couldn’t sell enough Coca-Cola in the country to stay in business, or they want to move to a new office building in the city they’re in, and they roll up that special purpose entity and close it down, and you’ve got no asset to collect against, and it’s not Coca-Cola.

Or the other one is right of first refusal. You find that a tenant has been given by a landlord or a developer years ago the right to have a right of first refusal to buy the entire building. So you go put the building on the market, and you get notified by the tenant that they have a right of first refusal, which means you go out, get the best offer you can get, and the tenant can buy it at that.

You say, well, why does it matter? It matters because what outside bidder is going to go through all the brain damage of figuring how much to bid for the building if they know all anybody has to do is meet their price and they have a legal right for the building?

BRUCE KIRSCH: Right.

PROFESSOR 2: Therefore, a building encumbered by a right of first refusal will never attract a top price, because it scares away most bidders. And those are the kind of horror stories that you run into. I don’t want to say it’s the norm, but it is why you have a knowledgeable person read those leases.

BRUCE KIRSCH: I agree. You know, when I did a very small real estate transaction, you go to the closing table, and then you’re presented with a stack of documents. And I guess that sort of the expectation is that you just sort of gloss over them and you sign the papers.

PETER LINNEMAN: Right.

BRUCE KIRSCH: But I mean, if you’re really taking it seriously, you should say, all right, guys, leave me alone for a couple hours. I’m putting my net worth on the line here, and I’d like to read these.

PETER LINNEMAN: Interestingly, in Germany, by law, they go to the opposite extreme. By law, you have to have a notary read everything in the contract and all attachments, which can often be quite lengthy, like leases can be attachments, has to read them all out loud in the presence of a corporate officer, because they don’t want, under their law, anybody to come back saying, well, I didn’t know.

BRUCE KIRSCH: It’s not a crazy thing to do.

PETER LINNEMAN: Yep. It’s a– no, I think it’s a– think the German is a bit extreme, but it does cut out this, gee, I didn’t know, right?

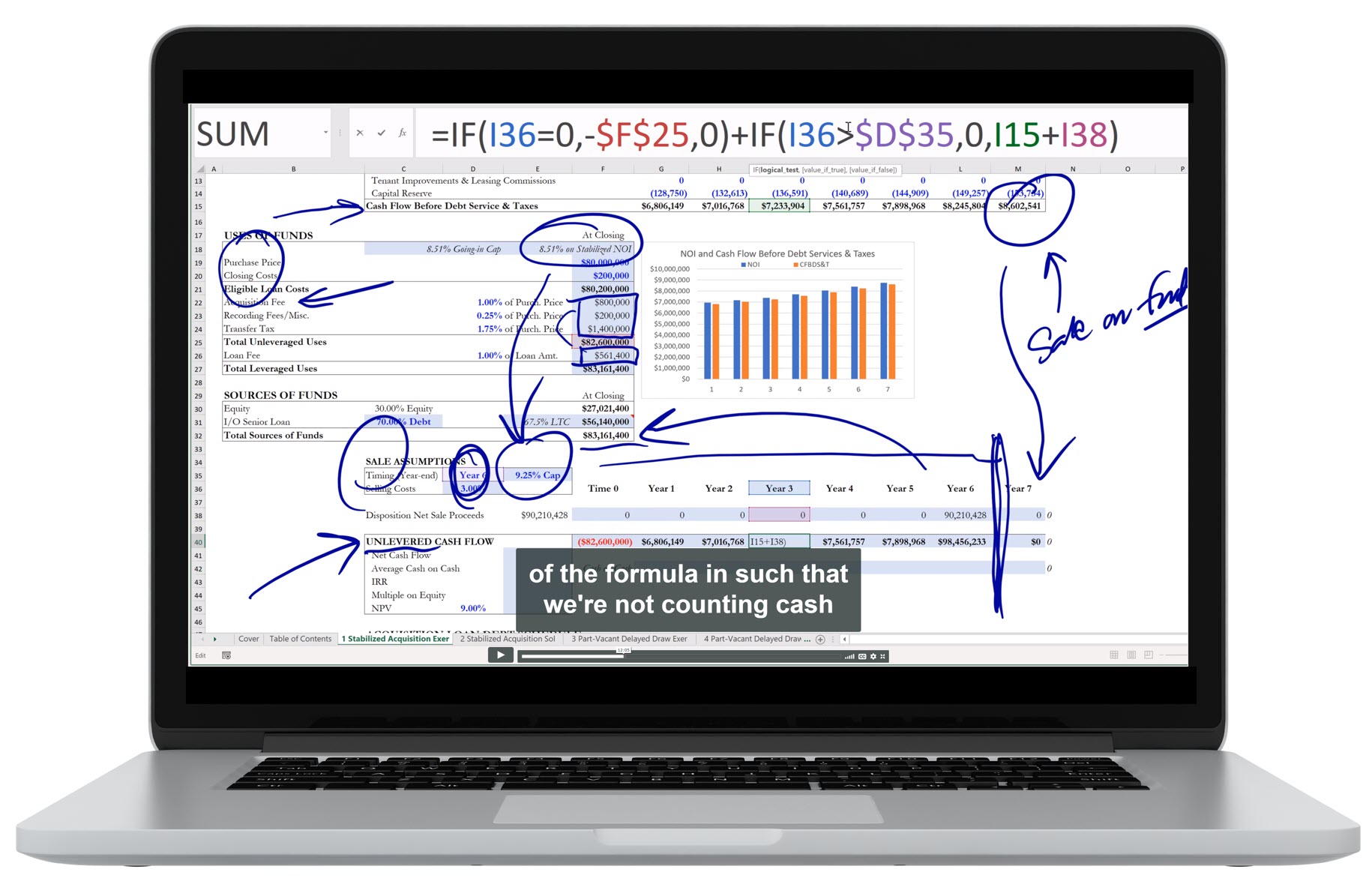

Excel Figure and Exercise Solution

Key Terms

To view the definition, click or press on the term. Repeat to hide the definition.

The owner/landlord of a property.

The tenant of leased space at a property.

Property operating expenses that change in proportion with the level of building occupancy. Examples include:

– electricity

– telephone service

– sewer rents and charges

– water and oil/gas

– repairs and maintenance

– janitorial and cleaning supplies and service

– elevator maintenance contracts

– shuttle bus service and maintenance

– fitness center equipment maintenance and replacement

– accounting fees for reimbursements

– common area snow removal (variable due to unpredictability)

– common area landscaping and plants.

Property operating expenses that do not change based on the level of building occupancy. Examples include:

– management fees

– management office rental value

– common area electricity

– supplies, uniforms, dry cleaning

– insurance premiums

– security

– concierge

– painting of common areas

– building employee wages and benefits

– payroll taxes

– legal fees

– window cleaning

– maintenance contracts for boilers, HVAC and other mechanical, plumbing and electrical equipment

– emergency generator service and maintenance

– licenses and permits

– trash removal/recycling

– pest control.

Tenant repayment to the landlord for tenant suite-specific expenses initially borne by the landlord.

The initial year’s rent for leased space.

How the base rent changes during the life of a lease; may be based upon inflation measures; may grow at specified dollar or percentage increments over the lease; or there may be no rent escalations in the lease at all.

A form of additional rent that specifies the percentage of the tenant’s gross sales revenue that the landlord receives in addition to the base rent and escalations; helps to align retail tenant interests with those of the landlord.

Any rent obligation of the tenant to the landlord under the terms of a lease other than base rent and base rent escalations. Percentage rent is a form of additional rent.

Property spaces available for use by all tenants, such as the lobby, hallways, roof deck, parking and outdoor landscaped areas.

Upkeep of shared spaces such as the lobby, sidewalks, parking areas and outdoor landscaped areas.

An upper bound specified in the lease that limit the extent to which operating expense items can rise during any single year, or over the term of the lease. These caps may be negotiated for any component of operating costs, including utilities, property taxes, and insurance.

The defined base year operating expense amount above which increases in expenses may be borne by the tenant.

The year in the lease at which base levels of operating expenses are set, and above which increases in expenses may be borne by the tenant.

Interior construction performed to make a tenant’s space fully operational.

The landlord’s cash contribution to the tenant’s approved scope of work; typically quoted in $ per square foot.

No rent is paid during the first weeks, months, or years of the lease. A negotiated concession used to induce a tenant to agree to other lease terms.

Rent after all operating costs are paid.

A lease structure, most common in retail properties, in which the tenant pays all operating (and frequently capital) costs, including insurance, utilities, and property taxes in addition to the contractual base rent and escalations.

Leases that make the tenant bear the cost of certain operating and capital items, shifting the risk of increases in such costs from the landlord to the tenant, altering the ownership risk of the property.

Annual rent, net of: unrecovered maintenance and operating costs (property taxes, insurance, utilities, etc.), the amortized value of free rent, the amortized value of leasing commissions, and the amortized value of TIs.

When a tenant vacates a space but still pays their rent. This prevents potential competitors from moving into the space.

The lease or purchase option of additional future space near or adjacent to the tenant’s current location in order to satisfy the tenant’s growth at the same location.

A lease term that prevents landlords from leasing to competitors of the lessee.

A clause that states a tenant will only lease if other named tenants remain in the center.

Restrictions imposed by the landlord that prohibits the tenant from opening other stores within a certain distance of the subject property.

Chapter Headings

- Economic Terms

- Rent

- Marketing Budget

- Utilities, Insurance, and Property Taxes

- HVAC – Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning

- Security and Property Maintenance

- Tenant Improvements

- Free Rent

- Capital Costs

- Net Rent

- Non-Economic Terms

- Signage

- Going Dark

- Hours and Days of Operation

- Length of Lease

- Expansion Rights

- Usage Restrictions

- Sublet Rights

- Location Assignment

- Detailed Description of the Space

- Tenant Mix

- Parking

- Recourse and Security Deposit

Learn about REFAI Certification

< Ch 3 | International Real Estate Investing

Ch 5 | Property-Level Pro Forma Analysis >

Table of Contents

Index

Buy the Book