Overview

Listen to this narration if you prefer

Chapter 19 discusses real estate private equity funds, which emerged as a capital source to fill the need for equity in the real estate business. Historically, real estate was purchased and developed with significant amounts of debt and very little equity.

Summary

Until 1986, U.S. income tax laws allowed property owners to depreciate structures over a 15-year period. These compressed depreciation schedules resulted in negative taxable income to property owners. Owners could sell these tax losses on a forward basis to people, such as doctors and dentists, who were looking to shelter their professional income, allowing the owners to easily raise equity without having to put much or any of their own at risk. Even real estate developers were able to sell the tax losses on a forward basis prior to the start of construction.

In 1986, Congress extended depreciation schedules and prohibited the sale of tax losses, except for low-income housing and historic preservation. As a result, the primary source of equity for real estate projects disappeared. In the early 1990s, real estate lenders realized that they were mispricing their loans and began offering only 50-70%, rather than 90-100%, loan-to-value mortgages. This meant that large chunks of equity were required to own or develop real estate. In this new environment, investors with equity certainty often had a distinct advantage, which led to the creation of real estate private equity funds. Such funds raised large pools of capital prior to investing to ensure ready access to equity.

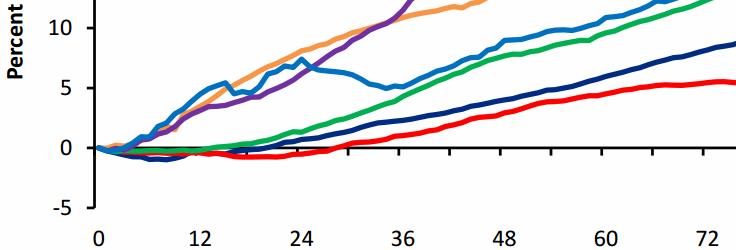

The real estate private equity business started in 1988 with the first Zell-Merrill fund. Today there are perhaps 2,000 professionals working in the business (excluding accountants), versus approximately 50 in 1992. Today, the industry is mature, with up to $125 billion in equity commitments raised annually and generally invested over three-year periods.

Pension funds, foundations, university endowments, and high net worth individuals are the entities which invest in real estate private equity funds. The minimum equity investment commitment is at least $1 million and is drawn down from these funds on an as-needed basis during the 3-4-year investment period. Investors invest in a limited partnership managed by the fund sponsor, who serves as the general partner responsible for all operations. A typical return target for these funds is a 20% IRR and a 2.0x equity multiple over the life of the investment. However, in light of the 2008-2009 Financial Crisis, these returns have crept down significantly. The typical fund promises to liquidate all property holdings within 7 to 10 years, as investors like knowing that they will get their money back. However, to avoid selling into a bad market when the fund’s life ends, sponsors and investors generally can agree to extend a fund’s life up to a period of three years, pending a vote of the investors.

Listen to this narration if you prefer

Fund sponsors are generally permitted to raise a new fund after 85% of the existing fund’s capital is invested, enabling them to minimize or eliminate downtime between funds. The sponsor also invests its capital in the fund. The amount invested by the sponsor can range from 1 to 3% for first-time fund managers, to 25 to 50% of total equity commitments.

There are three broad groups of real estate private equity funds today: those associated with investment banks; those associated with investment houses; and dedicated real estate players. Brand recognition is a huge factor in the investing business and has become increasingly powerful in attracting limited partner investors.

A return waterfall details how cash is split between the investors and the sponsor. A typical fund will provide investors (including sponsors who invested in the fund) with an IRR-based preferred return on all commitments drawn. These preferred returns range from 7 to 11%. If the returns exceed the preferred return, then these additional profits are split 80/20 (with 80% of the profits going to the investors or “the money”). The 20% of the profits given to the sponsor is called a carried interest or promote. This structure provides an incentive for the sponsor to generate oversized returns.

The sponsor’s promote is typically structured in one of two ways. In the most common structure, the sponsor and the investors split profits 80/20, as long as the investor receives at least the annual preferred return. Alternatively, there may be an 80/20 split only on profits in excess of the preferred return. Obviously, the sponsor would prefer the first methodology but usually agrees to the second. Another option that many funds feature is a catch-up provision. Such a provision allows a sponsor to split cash flows 50/50 (or at some other accelerated rate) over the preferred return until they have received 20% of all profits, after which the economics return to the 80/20 split.

In addition to their promote, fund sponsors also receive an annual management fee. The fee is typically 1 to 1.5% of committed equity (whether the money is drawn or not). As money is returned to investors this fee declines; that said, the fee is hopefully replaced by the fees earned from the subsequent fund.

Questions

These are the types of questions you’ll be able to answer after studying the full chapter.

1. Why is ready access to equity helpful?

2. What are the three broad groups of real estate funds today and what are their comparative advantages?

3. Explain the purpose of a catch-up structure for a sponsor after a preferred return hurdle is met.

4. Assume a $100MM fund with an 8% annual preferred return, where the sponsor contributed 10% of the fund’s capital. Assume that the fund liquidates in one year after earning $32MM in profits. What would the sponsor earn assuming a 20% promote?

Audio Interviews

Real estate private equity funds versus syndications (7:16)

BRUCE KIRSCH: Real estate private equity funds, or PE funds, are a much-talked-about part of the business. But they are a relatively recent entrant onto the scene, having started just in the late 1980s. What’s the difference between what we think of today as a real estate private equity fund and another vehicle that’s been around for a much longer time, real estate equity syndication?

PETER LINNEMAN: When we talk about a syndication, which still exists– I mean, syndication is very much still a common mechanism. Syndication says, here is the property, 712 Manhattan Lane. Very specific property, and I’m going to go out and raise money from a pool of investors for that specific identified property and identified pricing and identified management terms.

Where it could be pooled, I could have three properties in there. But it’s not blind. You know exactly what you’re getting, and that’s what you’re signing in for.

What a private equity vehicle is is different. It says, what I’m going to do is go out and raise money from investors based on my reputation, my strategy, my track record, my credentials, my investment objectives. I’m going to raise the money ahead of time. I’m not going to have any properties I can show you. All I can show you is who’s my team, what’s my philosophy, what’s my track record, here’s my reputation.

Here’s where we all went to school. Here’s what we did in our prior life. And you give me money ahead of time with which I then will go out and invest on your behalf, on behalf of this pool of investors. And it’s very much a trust-me vehicle. It’s a blind vehicle. You don’t know what they’re going to buy.

You know who they are, and up to personnel leaving you know what their strategy is up to them changing. But you’re not buying specific properties. You’re buying into a concept in a private equity vehicle.

And you’re obligated to provide money under contractual terms at contractual fees, contractual profit splits, contractual governance. The governance usually is the manager who’s raising the money gets to decide how to operate the property and how to invest the money and how to dispose of the properties at their sole discretion, as long as they’re a good fiduciary and they’re not doing fraudulent things. So they’re very different.

The private equity is a much harder vehicle to raise money for, because it’s a trust-me vehicle, as opposed to a syndication, or a traditional syndication, where what you’re buying. You still have to trust me to manage it well. You still have to like the pricing. But at least you know what you’re buying.

But the hard part of a syndicate is, well, I don’t have the money with which to tie up the property. And so what happens in the traditional syndication that’s made it difficult is I don’t have the money, but I have to convince the seller to let me tie up their property while I go put the syndicate together and market the property. And that may take three months, six months to get the money corralled and put together documents.

Meanwhile, hold on, I’ve got a sole right to buy your property. The beauty of private equity is it may take me two years to raise the blind pool, because it’s a slow process. It may take me much longer to raise a blind pool than a property-identified syndicate.

But once I’ve raised it, I can go to sellers and say, here’s the money. I’ve got the money. I’ve put the money down. They don’t worry about, gee, I wonder if he’ll be able to raise the money. So they each have their pros and cons as a way to operate.

And the thing I would close that comment on is, increasingly, private equity funds are almost becoming like brand-name money managers. There’s a few– I think there’s a wave of consolidation underway of brand names. Not just reputation of good firms, but brand name. There are a lot of good firms, but there are only a few brand names.

And the business in private equity, since it is very much a trust-me business– it’s a very much, make sure you’re comfortable with who you give the money to and nobody will ever second guess you– it’s reputation plus brand. You’re starting to see firms like Blackstone and Colony, and maybe Apollo and Carlyle and a few, go beyond reputation to brand, whereas a lot of people who have very good reputations– very good reputations– are finding it harder to raise a private equity vehicle and are looking more to syndicate.

BRUCE KIRSCH: Now, in a private equity fund, typically there is a finite life to the fund. Is that typically the same with the syndication, where they say, here is the property, and we’re going to hold it for five years? Or is it more open-ended?

PETER LINNEMAN: Syndicates tend to be more open-ended. They can have a finite life. But more typical in a syndicate is something that says, this is the owner. This is the operator. They get to decide, usually in their sole discretion, when the right time to sell is.

There might be some outside date of 10 or 15 years. Or there may be something that if 70% of the money says you have to sell, you have to sell. But it tends to be a longer-lived, more open-lived phenomenon.

When you look at private equity, remember, it’s a pure trust vehicle. Trust me, I’m going to buy what you want. I’m going to sell what you want. I’m going to do all these things.

The pushback then becomes, OK, I’m only going to give you three or four years to invest the money, and I’m only going to give you maybe seven or eight years total to have my money after which you have to give it back, no matter what, unless I is the investors say otherwise.

So as a trust vehicle, there are more restrictions put on it. The greater you have to have trust. Trust is fine, but. And so syndicates generally have longer lives and more flexible lives.

How real estate private equity funds have changed for the better and for the worse (5:19)

BRUCE KIRSCH: In what ways have real estate private equity funds changed since the 1980s for the better? And have they changed it all for the worse?

PETER LINNEMAN: For the better, without a doubt, is they’re more transparent. The original private equity funds tended to be you give me your money on this. I’m going to do the right thing with it, but don’t ask me to report a lot. If you want reporting, go get in a REIT or go to a private syndication.

I’m not here to report. I’m here to invest. And so don’t ask for a lot of reporting and don’t ask for a lot of transparency.

I think driven by the increased transparency over the last 20 years that’s come about in the public market, you’ve seen the private equity firms have also had to increase their transparency. They still are not as transparent as a publicly-traded company, but they’ve come just enormous distance on transparency. What do I own? What do I think it’s worth?

Why do I think it’s worth that? What is my plan to do with it? Do I have debt on it? Do I own all of it? Do I own part of it? Is it above water? Is it the low water, all those kind of things.

So the biggest change I’ve seen for the best is much greater transparency. Stan Ross and I wrote a paper 10, 12 years ago. Stan is kind of a legendary guy in the business. And our paper was really admonishing our friends, in many cases, to, if you want people’s money, and you really want it for a long time, and you want the opportunity to flourish with it, get transparent on your own. And I think the industry heard us and has done a great job.

If you said what’s there a thing that’s probably happened to the worse, the thing that’s probably happened to the worse was not intentional, but it occurred. The notion of a private equity fund in the beginning was you, dear investor, pay enough fee that I can break even on my overhead, where I’m paid a minimal salary, and all my employees are paid market wages, and I pay market rent for my space and so forth. But the point is, I’m not making any money from the management fees.

Where I’m really going to make my money is from the carried interest from the promote, my share of the profits from my sweat. And in that situation, while interests weren’t perfectly aligned, they were pretty well aligned. Gee, on a $100 million fund, I was only going to get a million and a half in fees. If you went through my overhead, my overhead was a million 4, because secretaries have to be paid and analysts have to be paid and associates have to be paid and so forth.

I was making no money from the management fee. All the money that I was going to make was being paid from my share of the profits, and I was highly incentivized to generate profits. And in fact, think of $100 million under management.

You’re going to generate a million and a half in fees. You’ve got employees. You’re a person who maybe could go to work for somebody and make a million dollars. There’s no way as a private equity manager with only $100 million you’re going to get paid what you could get paid, but you’re going to get a share of the profits. Very well aligned.

As these funds have grown, you’ve got funds that have $10, $20 billion of assets under management. Well, now, you start doing what– even a 1% fee on $20 billion is $200 million. You’re going to hire a lot of analysts for $200 million.

And suddenly, you’re making enormous money as the manager, even if you never make it as an investor by the profit share. Now, that doesn’t mean they don’t want the profit share, but it reduces the alignment. So as these private equity funds have gotten large, and I mean large in their success, the economies of scale of operation have made them highly profitable, very highly profitable, even if they never generate profit for their investors that give them a carried interest.

That’s probably the worst thing that’s happened. Now, it doesn’t mean there’s no alignment, it just means– it’s just like it’s not perfect transparency, and transparency was the big gain. It’s not like there’s no alignment of interests, but the interests are not as well aligned today as they were when all these funds were small.

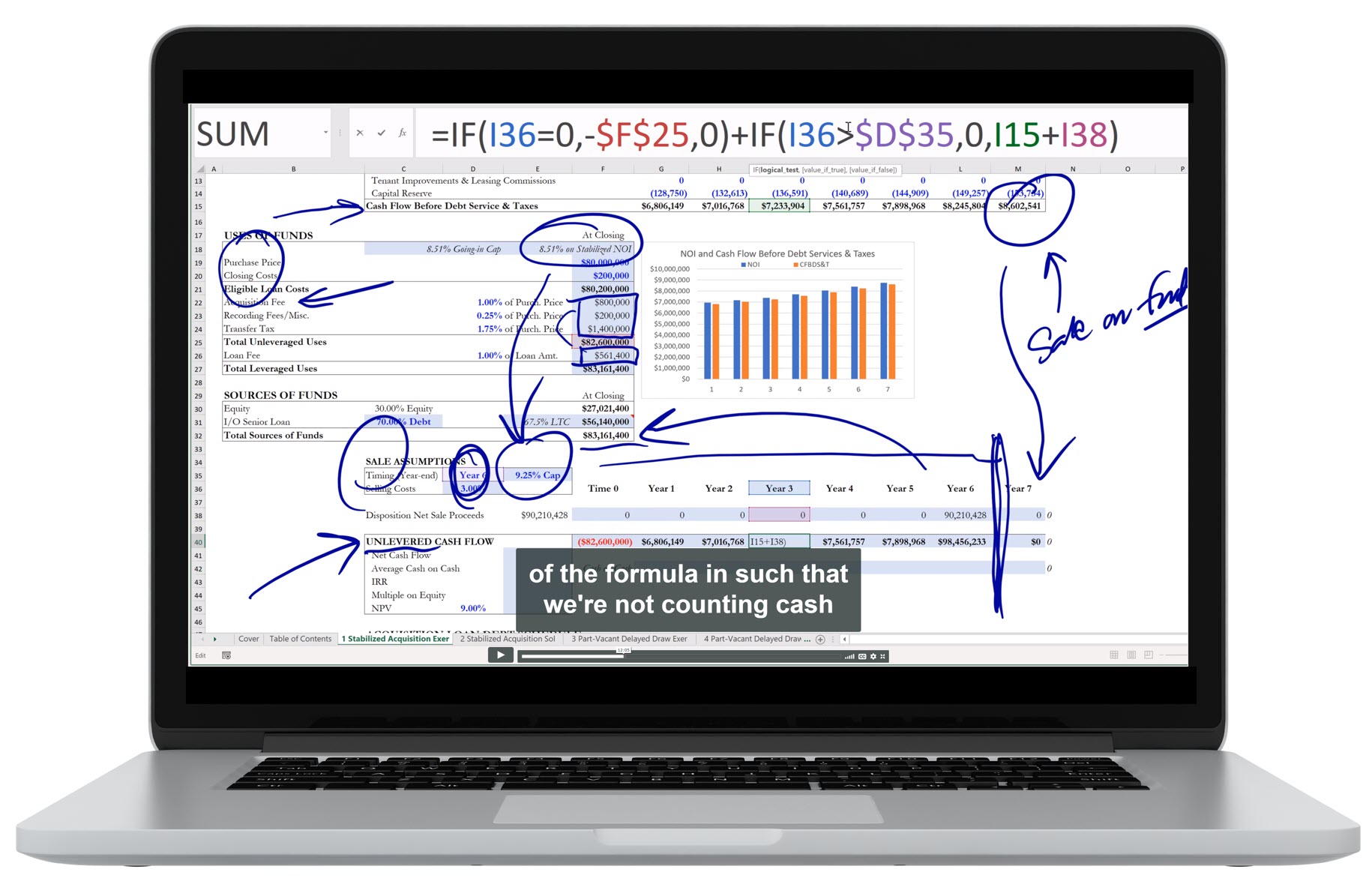

Excel Figures

Key Terms

To view the definition, click or press on the term. Repeat to hide the definition.

A major source of capital for the real estate industry; among the largest owners of real estate in the country; raise large pools of equity prior to investing to ensure ready access to equity.

Small investment group (relative to the size of PE funds) that are put together for a single pre-identified real estate transaction.

A limited partner’s obligation to provide a certain amount of capital to a private equity fund for investments.

When a private equity fund calls for a portion of an investment commitment be transferred to the fund.

The company that raises the fund and serves as the general partner (GP) responsible for all operations.

The persons in a limited partnership responsible for the actions of the business, with the ability to legally bind the business, and who are personally liable for all the business’s debts and obligations.

A partner in a private equity fund whose liability towards the fund’s debts is legally limited to the extent of the partner’s investment.

A mechanism for how fund proceeds are split between the investors and the sponsor for the purposes of returning invested capital and paying out profits.

The minimum return to investors to be achieved before a sponsor carry is permitted; this preferred return is typically an IRR-based hurdle rate and is usually 7-11% annually.

The profit threshold above which the fund profits are shared according to the carried interest arrangement.

Pro rata/proportionate to the amount of one’s cash investment to the total investment amount.

The fund sponsor entity’s share of excess profit above the preferred return, with which no cash investment is associated. Also known as “sweat equity.”

Only the profits in excess of the preferred return distribution.

A method of truing up the payment of IRR-based profit splits based on measuring accrued earned amounts and funding these earned amounts with distributions.

A private equity fund distribution provision that allows for the sponsor to be caught up to the same rate of return as the Limited Partners.

A protection mechanism put in place by Limited Partners that returns any excess share of total profits to “the money” to comply with a percentage cap on distributions received by the sponsor.

Chapter Headings

- Evolution

- A Bit of History

- Who Are They?

- Investment Banks

- Investment Houses

- Dedicated Real Estate Players

- Return Waterfall

- Investor Protections

Learn about REFAI Certification

< Ch 18 | Real Estate Owner Exit Strategies

Ch 20 | Investment Return Profiles >

Table of Contents

Index

Buy the Book