Overview

Chapter 16 provides a detailed overview of the commercial mortgage-backed security (CMBS) industry. In the 1970s, real estate loans were primarily made by local commercial banks and life insurance companies, when 70% of U.S. assets were held by these two types of institutions. Today, approximately 65% of all U.S. assets are held by pension and mutual funds. CMBS allows the real estate industry to access these two forms of capital for real estate debt.

Summary

Listen to this narration if you prefer

The CMBS market allows originators to make loans that fit specific terms with their capital base and to then package these loans into large pools that are sold to investors seeking yield. Specifically, if a lender can originate $500 million in loans each quarter, but only has $500 million available to lend, they cannot lend beyond their current portfolio. Therefore, rather than tie up their $500 million for the next 10 years, while their origination expertise sits idle, they can package and sell their existing loans. In essence, this allows them to capitalize on their underwriting skills by originating more loans with the sale proceeds. Originators create a new company called a special-purpose bankruptcy-remote entity (SPE) that ultimately owns the mortgage pools and facilitates their sale. The originators transfer ownership of the loans into the SPE in exchange for 100% of its ownership. They then sell interests in the SPE to pension and fixed-income mutual funds. By focusing on large institutional fixed-income capital sources, which desire long-term assets, originators generally obtain better pricing for the SPE than if they only marketed to dedicated real estate money sources.

The investment banks developed large marketing arms to sell these securities and were able to generate significantly more value from the securities by breaking them up into tranches. If the loan pool is large enough, it is possible to sell multiple ownership classes in an attempt to appeal to a much broader set of investors. Tranching involves the creation of many separate ownership claims on the stream of cash flows from the mortgages. Each tranche has a different priority claim and payoff structure on the underlying mortgages. The rating agencies then apply various models to determine the likelihood of losing money for each of the claims. Typically, the 60% most-senior claims on CMBS cash flows receive AAA ratings, with another 10% rated AA, 10% rated A, 10% rated BBB, and roughly 8% in the BB range. The last 2% is the most subordinated ownership claim, effectively the common equity of the SPE. Using this structure, the investment banks are able to sell these pools of securities for greater amounts than if they were not divided into tranches, given the appetite for AAA-rated paper. Defaults impact the lowest-rated tranche first, and work their way up the stack.

Securitization allows for a return to specialization for each step in the process: loan origination, loan packaging, selling and marketing the issuance, holding the loans, and servicing the loans. The management component of the entity is typically outsourced for a fee to two different specialists: the servicer and special servicer. The servicer is responsible for making sure the borrowers are performing in accordance to their loan documents and for taking appropriate actions if the borrower is in default. The special servicer takes control of the administration of any non-performing loans.

The CMBS market crashed spectacularly in late 2008 after an equally spectacular run from 2003 through mid-2007. The cause of this crash and subsequent CMBS market freeze was remarkably simple: low-quality mortgage pools were oversold by investment banks and overrated by the rating agencies. When institutional investors realized that they were not holding what they expected in terms of credit, they fled to safety, and the market experienced a shock.

Questions

These are the types of questions you’ll be able to answer after studying the full chapter.

1. How can value be created by pooling and tranching real estate loans into securities?

2. Why did the CMBS market crash in late 2008?

3. Explain the different roles of a servicer and a special servicer.

Audio Interviews

The biggest myth about CMBS (7:30)

BRUCE KIRSCH: Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities, or CMBS, are a relatively new financing innovation. And what they’ve done is they’ve helped to create a more liquid and more plentiful debt market for commercial real estate. The essence of a mortgage-backed security is bundling and packaging of multiple mortgages from various properties into a pool, and then issuing shares in that pool.

And so investors will purchase the shares seeking a targeted yield on their investment from the scheduled interest payments, and then return of their principal at the end of the term of issuance. And all of this, when it’s said and done, will blend into a final IRR by the end of the timeline.

Now, this is pretty complicated. And so it’s easy to misunderstand how this all works. What do you think is the biggest misconception about what CMBS is and how it functions?

PETER LINNEMAN: That you can destroy risk. You can’t destroy risk. The mortgages have underlying risk, both because each mortgage is backed by a specific property, and that property has risk relating to that, building related to that market therein, to that property type, and when that loan is due.

The other side of it is that you can’t change those by packaging them. Those risks exist. And there’s this mythology that somehow I can eliminate risk. I can’t eliminate risk. That risk exists.

I can redistribute that risk. I can say, Bruce, you take more of that risk, and I’ll take less. But the total amount of risk is still the same. So that’s the one big myth.

There’s probably a second huge myth, and it’s crushed the market in the late 2000s window. And that was that the risk of one mortgage is unrelated to the risk of another mortgage. So the way that these products were packaged and sold essentially assumed that if I put 10 mortgages into a pool, each of them had a risk of default that was unrelated to the other nine.

And the rationale went, well, one’s in an office building in St. Louis, and another is a shopping center in Tampa. The other is an apartment building in Boston, and the other is a warehouse in Seattle. How could those buildings have correlated risk? They aren’t competing with one another. Therefore, it’s not like one’s stealing tenants from the other, or the whole city goes down. Gee, the risks are uncorrelated.

Well, some of us wrote at the time, they are correlated. They’re highly correlated. They’re not correlated as a microphenomenon. Namely, the market’s fine, and one building’s losing tenants to another competitor. They’re not correlated in that sense. But they’re huge correlated in the macro sense. Namely, a bad economy, a bad US economy, will hit Tampa retail sales. It’ll hit Boston warehouse activity. It’ll hit St. Louis office activity, and it will hit apartments as well. It will hit everything.

When people are losing their jobs, they’re not buying as much at shopping centers. They’re not leasing as much office space. They’re not storing as many boxes in their warehouses. And they aren’t as aggressive as a renting apartment. So that the cash streams of all these properties have a general macroeconomic risk that’s highly correlated.

And secondly, they all have capital market risk. Namely, no one wants to lend. No one wants to invest. And therefore, when no one wants to lend and no one wants to invest, they’re all going to experience difficulty in their valuations and difficulty in their ruling over of loans at the same time, even though they’re different property types in different markets.

Now, these risks may not be perfectly correlated. St. Louis may not get hit quite as hard as Minneapolis or whatever, but they are highly correlated. And the risk models package these as if they were uncorrelated. And you may recall the phenomenon of flipping coins.

Imagine flipping 10 coins that are independent. You get a different kind of pattern of outcome than if you say, I flip 10 coins, but whatever one comes up, they all come up. The risk is very different in those two situations.

And these products have historically been priced and analyzed as if the risks are independent, when in fact, they’re highly correlated, driven by macro– not micro, but macroeconomic trends and macro capital market trends. So their micro property may be uncorrelated, but the overarching risk is highly correlated. That has been probably the biggest myth that’s gone out there.

BRUCE KIRSCH: I think that it’s not even that far-fetched to be able to see how they might be directly tied, though. Let’s say that you’ve got, in this pool, a commercial office building in Chicago. And in the same pool, you have an apartment building in New York. And the folks who are the tenants in the apartment building in New York, or some of them, work for the company that’s based in Chicago. And so while it might be a little far-fetched– well, what are the odds of that? Well, it does happen, right?

PETER LINNEMAN: Yeah, and when you think about retail, for example, it’s even more obvious that people who are buying stuff in Tampa, those companies whose goods are being bought are tenants in an office building in St. Louis. They’re tenants somewhere. And they’re storing their boxes somewhere in a distribution center. And their employees are living in apartments somewhere.

And so when you think of them that way, there is undoubted macro correlation. And in the United States economy, the world economy, not every place falls the same. But most places fall at the same time. Most places rise at the same time. Some rise more, some rise less, some fall more, some fall less. But that commonality of rising and falling means the risks are correlated.

The 2009 CMBS market crash and its ramifications (6:15)

BRUCE KIRSCH: What does it mean when people say the CMBS market crashed? Is that the same thing as saying that the overall real estate market crashed?

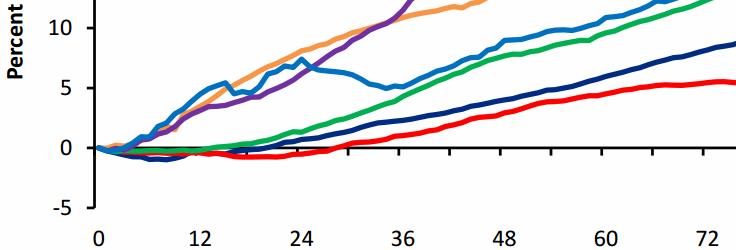

PETER LINNEMAN: No. I mean, they’re related, but it’s not the same thing. I think normally what people mean is CMBS went from, in 1990, probably doing a billion a year of issuing mortgages. It got up to $50 billion a year in mortgages by around 2000. And by 2004, 2005, 2006, and 2007, there were $120 billion, $160 billion, $200 billion, and $280 billion, respectively, being done in mortgages. This is a market that had really kind of slowly grown, had a little plateau and then exploded.

2007 is about $270 billion in new mortgages being written that are then put into CMBS and sold in a structure. By 2008, 2009, you’re back down to $4 billion. And that’s the crash. That is, it just didn’t issue anything.

The old ones were out there, but it didn’t issue anything new. And the reason it didn’t issue anything new is the credit crisis had created a complete lack of confidence in the underwriting of CMBS issuers. There were skyrocketing delinquency rates and default rates that went from essentially zero to 10% in a matter of a year or so.

So instead of having half a percent of the loans in some type of special situation, within a year or two, you had 10%. And people just lost all confidence. The financial crisis made things very uncertain, in general. No one wanted to make commitments. And the interest rate scenario was very volatile.

And all that just said that you couldn’t issue mortgages and put them together in a CMBS because there was nobody to buy them. If there was nobody to buy them, there was nobody willing to make those loans. And since there was nobody willing to make those loans, you lost the $270 billion source of financing.

You can imagine you were expecting to be financed in 2008 or 2009 or 2010 as part of a $200 to $300 billion sector that did zero, for all intents and purposes. That put tremendous pressure on refinancings. It put tremendous pressure on the pricing of real estate because people who thought they would be easily able to get loans suddenly couldn’t get loans.

They were scrambling for equity. They were scrambling in every way. Pricing pressure came on, which increased the delinquency and default rates. So in that sense, they were symbiotically related.

By 2012, year-end, the market had gotten back to where about $45 billion in the US of new issued CMBS. So you were back to the level that you were in the late ’90s or very early 2000s, but you were nowhere near this peak. And I think most people believe 2013 will come in at somewhere between $45 and $60 billion. It’s a sector that’s still rebuilding confidence among the investor pool. And that’s going to take some time. Trust lost is not so quickly trust regained.

BRUCE KIRSCH: On that note, are there more restrictions, more requirements for transparency this time around for documentation, and making things clear and easy to understand for potential investors?

PETER LINNEMAN: There’s a lot of subtle tweaking, legal tweaking of the documents that have occurred. The more substantive thing that’s occurred in 2011 and 2012 is a return to a sort of old-school underwriting of a mortgage. Income that’s not in place, I’m not going to give you credit for. If it occurs, great. It’s a cushion for the lender. But what I see as income is all I’m going to treat.

I’m only going to treat income from credit tenants, in some cases, as income. Even if you’ve got income from other people, if it’s not from credit tenants at a shopping center, I’m not going to count it I’m not going to do 1.1 interest coverage. I’m going to insist on 1.3 times interest coverage– a bigger cushion.

I’m not going to rely on appraisals to tell me what a mortgage worth. I’m only going to give a mortgage if it’s a new purchase, and therefore, it’s a real transaction. Or I’m not going to include mortgages where you’re refinancing an existing mortgage, but taking more than the original mortgage out. That is, no refinancings that allow the borrower to take away proceeds.

There have to be reserved for tenant improvements. There have to be reserved for capital expenditures. Or else, I’m not going to make the mortgage. So it’s kind of a return to old-school underwriting.

And as markets get more competitive and people start chasing loans, both the underwriting and the technical stuff, the legal stuff, gets chipped away at it– always does in every market. CMBS is no different in good times. We’re still in not such great economic times, so still pretty decent in that regard.

BRUCE KIRSCH: No.

CMBS servicer and special servicer roles (3:08)

BRUCE KIRSCH: Prior to their marketing, CMBS pools are typically separated into tranches, or slices, of ownership that create an ownership hierarchy, in which the owner of the most senior tranche, or slice, sits in the safest position, with respect to the receipt of payments and the return of their principal. In the case of defaults from properties that are represented in the CMBS pool, what determines how much the CMBS special purpose entity will accept for a foreclosure sale on one of those distressed loans?

DR. PETER LINNEMAN: Well, when the original CMBS is set up, it has this pool of mortgages. And it has, if you think about it, two different management teams. These management teams are always outsourced to special vendors.

The servicer, the usual servicer, is the outsourced management paid as a matter of fee for all normal stuff. Normal stuff is collecting the interest and principal payments, recording, keeping track of amortization, sending out bills, sending out payments to the various tranches that own claims on it, all the normal processing. And they receive a fee for that.

In addition, there’s sort of a management team that’s been already engaged in case anything other than normal happens. And that’s referred to as the special servicer. And there’s very specified terms about when the special servicer takes over responsibilities and what their particular responsibilities are.

But it’s sufficient to say that when the kind of scenario you say– somebody isn’t paying, somebody is paying late, somebody tells you they aren’t going to pay, or they only pay part of their bill– as a general matter, the special servicer comes in. And when they come in, their fee starts getting triggered. And these people are not hired to process paperwork, like the normal servicer.

They’re hired to deal with problems, usually on an incentivized basis, where they’re getting some fixed fee, plus something related to how much they recover or restructure. And they’re the party put in charge of negotiating and determining, do I settle with you– you, the borrower? Do I sell the loan? Do I restructure the loan? Do I stretch it out? Do I reduce the interest rate? And they’re given quite a bit of discretion, though they have an absolute fiduciary duty, is the easiest way to think about it.

Now, like everything in life, it gets a little more complicated than that in the actual implementation, but that’s the best way to think about what’s going on.

Additional Multimedia

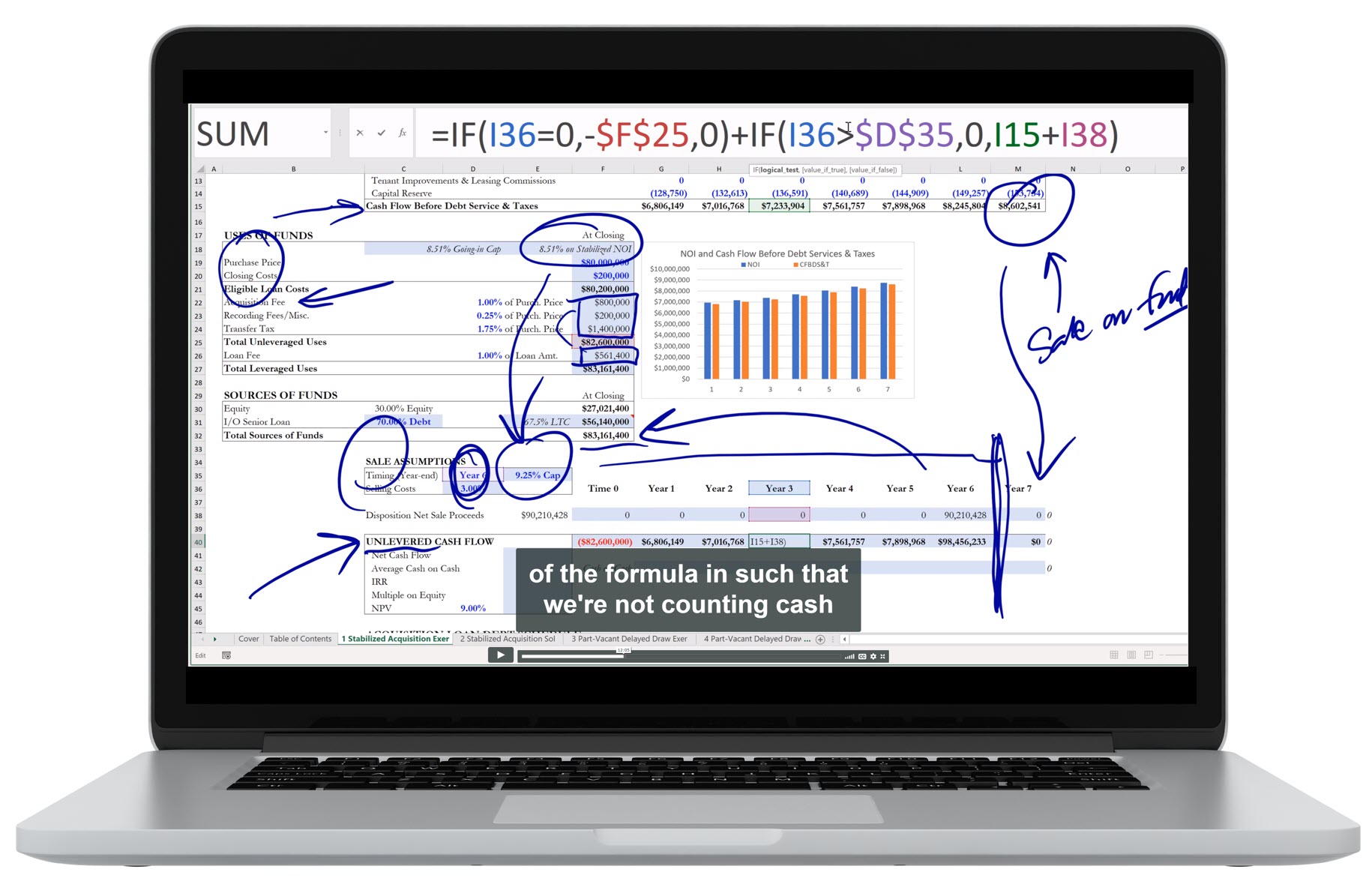

Excel Figures

Key Terms

To view the definition, click or press on the term. Repeat to hide the definition.

A tradable security that is collateralized by mortgages on commercial properties.

A special purpose vehicle that is formed to hold a defined group of assets and to protect them from being administered as property of a bankruptcy estate.

Service provider responsible for assuring that the borrowers are in compliance with their loan documents and for taking appropriate actions if the borrower is in default.

Service provider that takes control of the administration of any non-performing loans.

A discrete ownership class within a pool of CMBS mortgages.

Chapter Headings

- Capital Evolution

- Follow the Money

- How is a CMBS Issuance Created?

- How Do You Sell?

- Profit from the CMBS Packaging

- It’s about Specialization

- Creating Tranches

- Default Dynamics

- The Evolution of the U.S. CMBS Market

Learn about REFAI Certification

< Ch 15 | The Use of Debt and Mortgages

Ch 17 | Ground Leases as a Source of Finance >

Table of Contents

Index

Buy the Book